Leptospirosis – Springtime foe

Leptospirosis, or Lepto for short, infection peaks in the spring. Why? Lepto is caused by a spiral shaped bacteria called a spirochete. This bacteria is spread via the urine of infected animals which can contaminate both soil and standing water. Animals that can carry and spread lepto include raccoons, skunks, opossums and even mice and rats, especially in cities. These animals are less active in winter and the cold temperatures can kill the bacteria. Frozen puddles spread far fewer germs! Score one for the cold Connecticut winters. Unfortunately the bacteria can survive up to 6 months in the environment. Once the spring thaw arrives, it becomes more likely that active bacteria infect pets by entering through the skin or mucous membranes (eyes, nose and mouth).

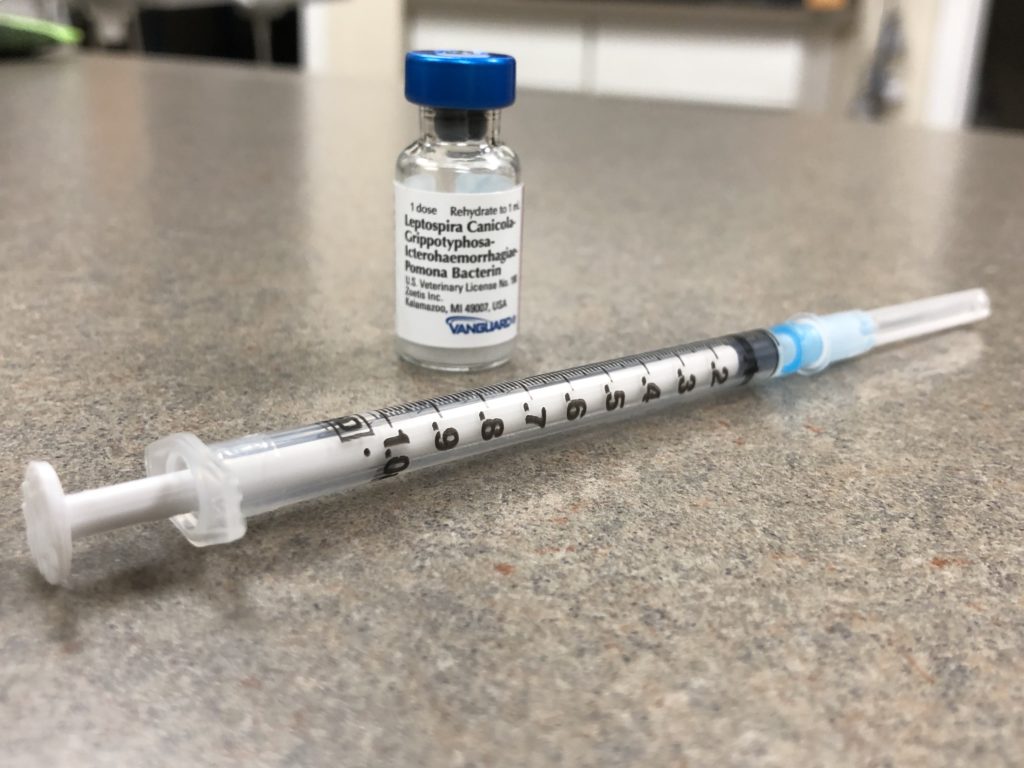

Once an animal is infected with Leptospirosis, they can shed bacteria and remain infectious for up to 3 months. Lepto is of particular concern because it is a zoonotic disease, meaning humans are also susceptible. Signs of infection in pets include joint pain, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, weakness, abdominal pain, excessive drinking and bleeding more readily. This disease then leads to sudden onset kidney injury in 90% of cases, while liver injury occurs in approximately 10-20% of cases. In humans, flu like symptoms occur with kidney and liver injury. Fortunately for our pets, veterinary vaccines against leptospirosis can provide some protection against infection. The initial vaccination protocol consists of 2 vaccinations a month apart the first year and 1 booster yearly thereafter. While vaccines protect against the four most common types of leptospira, there are over 20 different strains. Sadly, this means the vaccine is not always 100% effective. Research continues to find a more cross-protective vaccine.

When a veterinarian suspects leptospirosis, three different tests can be used for confirmation. Recent vaccination can make interpreting test results more tricky, so more than one test may occasionally be used. A snap test is a positive/negative test for anti-leptospira antibodies in the blood. This is the fastest of the tests and can be run right in your veterinary clinic. While this test is quick and easy, unfortunately it can produce a false positive in a recently vaccinated animal. A PCR or polymerase chain reaction test detects the DNA of the leptospira instead of antibodies. This test, however, may produce a false negative if the patient has been on antibiotics or the bacteria is no longer present it large enough numbers. Both blood and urine are tested by PCR because the blood will be positive early in infections and the urine 7-14 days after infection. MAT (microscopic agglutination testing) is another antibody test that detects the quantity, or titer, of antibodies against leptospira that are present in the patient’s blood. This test takes the longest to yield results, and is generally the most expensive, but it is considered the gold standard and most reliable test.

Leptospirosis is treated with antibiotics and supplemental support as needed. This includes IV catheter placement and fluid therapy, anti-nausea and diarrhea medications, and pain control. Especially because of the zoonotic nature of leptospirosis, the home environment should also be treated to limit sources of future infection. Try to remove all standing water sources and control the rodent population. Restrict your pet’s urination to one area away from standing water and keep other pets away from that area. If you pet urinates inside, wear gloves and disinfect with a household cleaner. Wash your hands after interacting with your pet. The good news is properly treated, Leptospirosis generally has an 80-90% survival rate. Prognosis depends on the amount of organ damage done. As always, any concerns you have over your pet’s health should be discussed with their veterinarian.